The Story So Far

The original Galaxy Zoo was launched in July 2007, with a data set made up of a million galaxies imaged with the robotic telescope of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. With so many galaxies, the team thought that it might take at least two years for visitors to the site to work through them all. Within 24 hours of launch, the site was receiving 70,000 classifications an hour, and more than 50 million classifications were received by the project during its first year, from almost 150,000 people.

Having multiple classifications of the same object is important, as it allows us to assess how reliable each one is. For some projects, we may only need a few thousand galaxies but want to be sure they're all spirals. No problem - just use those that 100% of classifiers agree on. For other projects we might want larger numbers of galaxies, so might use those that a majority say are spiral.

The task of the first Galaxy Zoo users was simpler than yours; all they had to do was split the galaxies into ellipticals and spirals and — if the galaxy was a spiral — record the direction of the arms. Using the data the project provided, we were able to prove that the classifications Galaxy Zoo provides are as good as those completed by professional astronomers.

Many projects are now underway using this data; you can read about the first few in our list of papers published and in progress, on the Galaxy Zoo blog and below. We’ve been successful in getting time on professional telescopes to follow up many Galaxy Zoo discoveries, too; the list currently includes the Isaac Newton and William Herschel Telescopes on the island of La Palma in the Canaries, Gemini South in Chile, the WIYN telescope on Kitt Peak, Arizona, the IRAM radio telescope in Spain's Sierra Nevada, the Swift and GALEX satellites, and the Hubble Space Telescope.

As the original Galaxy Zoo was the first time such a project had been attempted we were cautious, asking for fairly simple information about the appearance of the galaxies. Thanks to the overwhelming response we realised we could ask much more, so when we designed Galaxy Zoo 2, we took 250,000 of the best and brightest of our original sample of galaxies and asked more detailed questions. Once again, we were thrilled with the response (although a little more prepared than we were for Zoo 1) and in the 14 months the site was up Galaxy Zoo 2 users helped us make over 60,000,000 classifications. Along the way we added in more detailed images, taken from a patch of the sky known as 'Stripe 82' which the Sloan telescope repeatedly visited. Taken together, the Galaxy Zoo 2 database is already enabling scientists to understand how galaxies - including our own - form and evolve.

In previous Galaxy Zoo projects we have been looking at galaxies that are fairly nearby. Well, actually they are almost unimaginably distant from a human perspective, but by astronomical standards they're nearby in terms of the size of the whole universe that we can see. This latest incarnation of Galaxy Zoo uses data from the Hubble Space Telescope to go deeper than ever before: over to you.

Highlights of what we've learnt so far

Shapes and Colours

Over the past year, volunteers from the original Galaxy Zoo project — people like you — created the world's largest database of galaxy shapes. This database is already showing us surprising things about the nature of galaxies. For example, astronomers used to assume that if a galaxy appears red in colour, it is also probably an elliptical galaxy. But with your help, Galaxy Zoo has shown that up to a third of red galaxies are actually spirals. Similarly, there is a much larger number of blue ellipticals than previously thought, including a small but significant fraction of blue ellipticals that are in the process of forming considerable numbers of new stars — sometimes up to 50 times as many new stars as our galaxy.

From left to right : A normal (blue) spiral, a red spiral and an elliptical.

The Direction of Spirals

One of the initial projects for Galaxy Zoo, and the reason we asked volunteers to choose between 'clockwise' and 'anti-clockwise' spirals, was to see if more spiral galaxies rotated clockwise or anti-clockwise. If that turned out to be true, it would have profound implications for current theories, and would have forced scientists to completely rethink our understandings about space and time. So what did we find?

Thanks to Galaxy Zoo's database of volunteer-generated classifications, we now know that spiral galaxies do not have a preference for rotating clockwise or anti-clockwise, and that for the time being at least, our current theories of how the Universe works are still valid.

This may be something of a disappointment, but in another paper we were able to look at how neighbouring galaxies spin. It turns out that two galaxies which are close together are more likely to spin in the same direction than the opposite — and that tells us about how they start spinning in the first place. Intriguingly, there also seems to be a link between regions where galaxies spin together and how recently they've formed stars. Working out what's going on will keep us in a spin for a while yet...

Left image: A face-on spiral galaxy. You can clearly see the spiral arms and a central bulge.

Right image: This elliptical galaxy is composed entirely of a bulge of stars. There is no disk or spiral arms.

Barred Galaxies

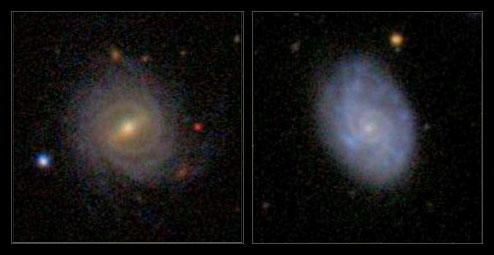

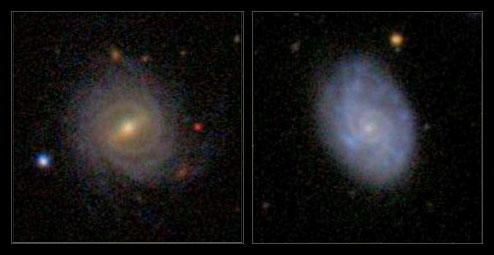

The first result from the Galaxy Zoo 2 classifications was on the properties of galaxies with bars. We used your classifications to show that redder disk galaxies with larger central concentrations (or bulges) are much more likely to host bars than bluer disk galaxies with smaller central concentrations. In fact the split is quite striking between the two populations of disk galaxies and suggests that bars play a very important role on the evolution of disk galaxies.

Left image: A barred spiral galaxy.

Right image: An un-barred spiral galaxy

Expect the Unexpected — The Voorwerp

One of the most exciting discoveries from the original Galaxy Zoo was something we never expected. Hanny Van Arkel, a Dutch schoolteacher and Galaxy Zoo volunteer, posted an image to the Galaxy Zoo forum and asked 'What's the blue stuff below?' No one knew. The object became known as the 'Voorwerp' — Dutch for 'object'. The original images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey couldn't tell us what it was, so we took follow-up telescope observations, in optical and ultra-violet light, as well as measurements from the Swift satellite.

The Voorwerp is shown above but you can read more about it and see additional examples on these Galaxy Zoo blog articles.

The Voorwerp is only one of the many interesting and wonderful objects that users found in Galaxy Zoo. Another example are the collection of small, round and apparently green objects that have become known as the Galaxy Zoo Peas. Teams of astronomers — and of Zooites — are working hard to follow up on these. It's something that is unique to a project like the Zoo. Computers will slowly get better at classifying galaxies, but looking at an image and asking 'what's that odd thing?' remains uniquely human.

We want you to know we use cookies to support features like login; without them, you're unlikely to be able to use our sites. By browsing our site with cookies enabled, you are agreeing to their use; read our newly updated privacy policy here to find out more.

We want you to know we use cookies to support features like login; without them, you're unlikely to be able to use our sites. By browsing our site with cookies enabled, you are agreeing to their use; read our newly updated privacy policy here to find out more.